Monthly Intentions

January: For peace. May the merciful Father bring an end to all discord between peoples of good will and grant His peace among all members of our local church.

February: For religious vocations. May God grant an increase to all religious orders who serve in the Diocese of Charlotte and grant zeal to all who are being called to a life of religious consecration.

March: For families. May God pour out an abundance of grace to every family in the diocese, that they may be domestic churches and dwellings of loving sacrifice.

April: For the homeless. May Christ, who had nowhere to lay his head, act in and through all the faithful in the diocese to provide for the needs of their brothers and sisters who lack housing.

May: For Mary’s intercession. May Mary, the patroness of our diocese, always look favorably upon our church and pray unceasingly for every member of Christ’s faithful.

June: For vocations to the priesthood. May the Lord give courage and strength to those who are being called to the ministerial priesthood, and may those who are called respond generously and faithfully.

July: For parishes. May God bless and enrich each and every parish in the diocese with His choicest graces and special protection, that they may be a visible expression of Christ’s body at work in the world.

August: For the sick and suffering. May God give comfort to the afflicted and suffering souls of the diocese and to those who are needy, that they may find in the generosity of faithful souls a remedy for their ailments.

September: For caregivers. May God grant all who care for the sick, needy, elderly, and imprisoned an outpouring of His love and mercy, that they may be strengthened in their apostolate and remain steadfast in living the Spiritual and Corporal Works of Mercy.

October: For parents. May God, through the intercession of Sts. Anne and Joachim, give strength and virtue to parents, that they may be true witnesses of faith and charity to their children.

November: For the faithful departed. May the Lord give eternal rest for all the faithful departed of the Diocese of Charlotte who lived and served faithfully united to the Church of God.

December: For children and youth. May Christ who came among us as a child strengthen the hearts and minds of our children, that they may faithfully receive the word of God by their ears and eyes, and profess their faith by their mouths.

Saint of the Month

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton

Feast Date: January 4

St. Jose Sanchez del Rio

Feast Date: February 10

St. Katharine Drexel

Feast Date: March 3

St. Gianna Beretta Molla

Feast Date: April 28

St. Dymphna

Feast Date: May 15

St. Charles Lwanga

Feast Date: June 3

St. Chi Zhuzi

Feast Date: July 9

Sts. Louis and Zelie Martin

Feast Date: July 12

St. Paul Chong Hasang

Feast Date: September 20

St. John Henry Newman

Feast Date: October 9

St. Agnes Le Thi Thanh

Feast Date: November 24

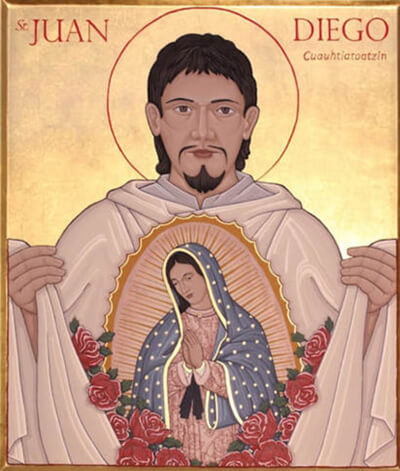

St. Juan Diego

Feast Date: December 9

Marian Art of the Month

ROME (C. 2ND CENTURY)

The protoevangelium of Genesis 3:15 makes clear from the dawn of salvation history the role that the Woman, the mother of the Redeemer, would have in God’s eternal plan for our salvation. Of course, we know that Woman to be Mary.

From its institution, the Church has understood and honored Christ’s Mother for her importance on Earth and in heaven. In seeking Truth through beauty, the Church has always incorporated her image in its teaching, devotional life, and in the liturgy itself. Few images of Mary or even Christ remain extant from those earliest centuries of persecution, but one striking image comes down to us from the Roman catacombs as a reminder of her pivotal place in the eyes of God and His people: this image of The Annunciation.

It is significant to note that perhaps the oldest surviving image of the Blessed Virgin does not depict the Nativity or her place at the foot of Christ’s cross, but the very moment of the Incarnation.

Before the Church Fathers had settled on the canon of Scripture, Mary’s greeting by the Archangel Gabriel as “blessed among women” was painted on the arched ceiling of the Catacomb of Priscilla. Once a rock quarry, this catacomb was used as a place of Christian burial for seven early popes and many martyrs beginning as early as the 2nd century. This decorative ceiling seems to date from the beginning of Christian usage – so early in fact, that some art historians doubt it shows Mary at all, though this same catacomb gives us some of the earliest paintings of the Madonna and Child and Christ the Good Shepherd.

The image is certainly Roman in style, but decay has stolen many of the details. What can we glean from what remains? Look carefully: A woman enthroned and crowned with a regal diadem, being addressed by an honored figure with a rudimentary halo standing bold upright before her and addressing her directly.

In the context of early Christian art, this makes perfect sense. In this image you can hear “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women” and young Mary the teenaged virgin betrothed to Joseph is seen by all who witness the sacrifice as the very Queen of Heaven whose fiat was uttered as the Word became flesh in her womb.

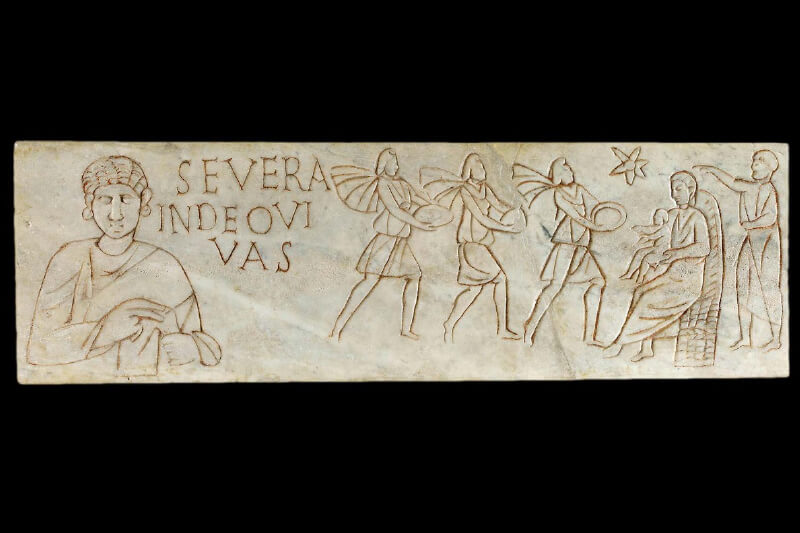

VATICAN MUSEUMS (C. EARLY 4TH CENTURY)

The Gospel narrative surrounding the Magi is not at all the fixation of medieval art that many modern scholars imply. In addition to the historical accounts of their journey found in Sacred Scripture, the Magi story is recounted in some of the earliest art and literature of the Christian Tradition and its oldest depictions further solidify the Church’s consistent witness to Mary’s honored role in the redemptive life of Christ.

Among the treasures of the Vatican Museums is this small slab (late third to early fourth century) from the cemetery of Priscilla. It is likely from the tomb of a child and bears an inscription wishing for the deceased to “Live in God!” Three figures in Eastern apparel, traveling in haste with their capes flying, are led by the star to Mary, who is seated on an elaborate high wicker chair, with the baby Jesus in her arms. Behind her seat is not St. Joseph, but the prophet Bàlaam, indicating the star, and thus the Messianic prophecy: “A star shall rise out of Jacob, a scepter shall spring up out of Israel” (Num 24:17). Kings from afar themselves are paying homage to the newborn King in the arms of His Queen Mother. Mary is not merely the mother of the human child Jesus, but part of a divine plan for salvation prophesied from the earliest of Scripture.

(LATE 6TH CENTURY)

The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai, Egypt, is the oldest active Christian monastery in the world. It houses an extraordinary collection of Byzantine manuscripts and art including a piece known as The Theotokos and Child between Sts. Theodore and George, dating from the late sixth or early seventh century.

As with many of the oldest icons, it is painted in encaustic, also known as hot wax painting. This wax technique produces a beautiful effect, enabling the use of gold and giving the painting a warm glow, but it also adds to the fragility of the work. Encaustic icons have suffered frequent damage from smoke and flame in a faith where devotion is marked by incense and candles. These factors make the survival of this striking ancient painting even more remarkable.

The icon shows Mary and the Christ child flanked by two soldier saints, St. Theodore to the left and St. George to the right. Above these are two angels who gaze upward to the hand of God, from which light emanates. This icon, a meeting of styles and peoples, depicts a pivotal moment in the history of the Church, capturing her incredible growth and spread into a truly universal body. Clearly influenced by classical Roman art, the figures bear an unmistakably Egyptian quality hearkening to mummy mask portraiture of a slightly earlier era. The lack of dept depiction found in most traditional icons gives way at the top, where the angels pull back and away – in awe at the hand of God. The saints are steadfast and ready to intercede on behalf of the viewer/supplicant, while Mary and Christ are enthroned and elevated, inhabiting a space visually closer to the Father. They draw our eye toward His hand, which in turn shines divine light back on Our Lady. Our gaze goes from earth to heaven and God directs it back to Mary, the officially declared God-bearer, mother to all the faithful as she is mother to His divine Son.

(C. 8TH CENTURY)

Heavily painted over, often crowned and frequently jeweled, the image of Our Lady known as “Salus Populi Romani” (“Protectress of the Roman People”) conveys even more an image of faith than it does of art.

After the Council of Ephesus in 431 A.D., in which Mary was acclaimed as the “Theotokos” (“God-bearer”), Pope Sixtus III erected at Rome a basilica dedicated to her honor. Now known as St. Mary Major, it is the oldest church in the West dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Tradition asserts that this image was made by St. Luke and brought from Crete at that time, but studies and style point to its likely oldest date as the post-iconoclastic period of the 700s and it has no tracible provenance before the 13th century. It is one of many, many images attributed to St. Luke in this period.

Why is St. Luke’s name attached to so many Marian icons painted so long after he lived? If Luke did paint these portraits of the Virgin, this meant that these images had an apostolic origin and could be seen as a visual representation of Luke’s own Gospel message – thus explaining and protecting these beloved paintings during times of iconoclasm. Our Lady, the greatest of saints, was assumed into heaven and thus had no bodily relic left behind for veneration – making her portraits even more important to the faithful.

“Salus Populi Romani” has grown even more beloved over the centuries. Clement VIII (1592-1605), Gregory XVI (1838) and Pius XII (1954, during the Marian Year for the centenary of the dogmatic definition of the Immaculate Conception) all crowned the image. These papal coronations recognize prayers answered in association with the icon and honor Mary for her share in Christ’s Incarnation and saving work.

St. Stanislaus Kostka, St. Ignatius Loyola and St. Francis of Borgia all had a particular devotion to the “Salus Populi Romani.” The icon has long been called upon in times of plague and illness and associated with several miraculous cures. After extensive restoration in 2018, it was most recently displayed and publicly venerated during prayers associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

(LATE 10TH CENTURY)

In 1950, Pope Pius XII proclaimed the dogma of the Assumption of Mary – body and soul – into heaven although it has been long held as a central Catholic belief. Mary’s assumption is often challenged by Protestant traditions for the seeming absence of scriptural evidence. Catholics point to the “woman” of the Protoevangelium of Genesis 3:15, Mary addressed as “woman” by Christ at Cana, and again from the cross when He entrusts her to the care of St. John, who in turn gives us the vision of “the woman clothed with the sun” in chapter 12 of his Book of Revelation.

Scripture also consistently presents Mary as intimately united with her Incarnate Son. From the earliest centuries, the Church recognized the importance of Mary’s role and asserted that her Divine Son honored her body, which had conceived and bore Him in full humanity and full divinity. Thus, it is consistent to assert that her body was preserved from decay and taken to heaven, anticipating the stated promised to all who believe.

Non-Scriptural accounts of Mary’s life and the writings of saints such as John Damascene (d. 749) make it clear that this was the understood end of the earthly life for the woman who was the very ark of the New Covenant.

Eastern tradition speaks of the Virgin’s entry into heaven as her “Koimesis,” and in the West it became known as her “Dormition” with the imagery emphasizing sleep rather than death.

The feast honoring this event was first recorded in the late seventh century when Pope Sergius (687-701) decreed it be celebrated in Rome.

We have grown so accustomed to Baroque depictions of the Blessed Virgin Mary floating upward on clouds that this little Byzantine ivory seems to almost tell a different tale. Still, this visual account is in keeping with the earliest iconographic traditions of the Christian faith. Non-canonical authors tell of Mary having been visited by an angel three days before she was to die. This time of preparation or “Transitus Mariae” allowed the apostles to attend her on her death bed, with both Peter and Paul standing witness among the angels. Christ Himself descends from heaven to carry his mother’s soul aloft – depicted as a newborn babe.

This ivory is so small it was likely produced in the late 10th century Constantinople as a hand-held devotional image intended for personal prayer and contemplation. This is not the two-dimensional art customary for so many icons of the time. It is carved with incredible emotion with the angels and Christ in deep relief.

The provenance does not extend back far enough to tell us who carved this work or who commissioned it, but its skill as well as its survival point to the significance of its use.

In the tradition accounted in “Transitus Mariae,” the apostles would subsequently bear Mary’s body in solemn procession to her grave where on the third day, angels would carry her body to heaven. The very message of this work is that even in death, the Blessed Mother always mirrors and reflects the glory of her Divine Son.

(13TH CENTURY)

The title “Black Madonna” or “Black Virgin” has been used in the West to denote many depictions of Mary with the Christ Child, both painted and sculpted, where the principal figures appear dark-skinned. Sometimes this is due to circumstances of the history of the image whereby the paint or varnish darkened over time, but often it was the intended depiction of the original artist who portrayed Mary and Jesus in keeping with the people of the region where the image was made.

Among some of the oldest extant Christian art, they were often produced in Coptic areas of Syria, Egypt and sub-Saharan Ethiopia and later taken to Constantinople. These Black Madonnas are frequently credited to the Evangelist Luke, who in some traditions was said to be a Syrian. Arguably the most famous Black Madonna is the icon known as “Our Lady of Częstochowa,” revered as the patroness of Poland.

Our Lady of Częstochowa is also called “Our Lady of Jasna Gora” after the name of the “bright hill” in Poland where the monastery that houses the image is located. The oft-repeated story is that sometime around 1384, Prince Wladyslaw, attempting to save the image from an invasion by the Tartars, was taking the painting to his birthplace in Opala. He stopped for the night in Częstochowa, where the image spent the night in a small church dedicated to Mary’s Assumption. The next morning the portrait was placed in a wagon, but the horses refused to move, and the painting has remained there ever since. Later, the image was damaged by a Tartar arrow and in 1430 Hussites (the Czech forerunners of the Protestant Reformation) stole and vandalized the image – and by some accounts were miraculously struck dead for this sacrilege.

Repeated overpainting and attempts to repair the icon are said to have been unable to cover the scar. This could easily be the case, as the Byzantine encaustic technique of painting with wax and resin had been lost to medieval painters.

Science and art history show the current image to be 13th century Byzantine in form and composition – almost certainly based on an icon from Constantinople that had been venerated in a church in the Hodegon Monastery quarter dating to the fifth century.

It is a traditional Eastern icon composition known as a “Hodegetria” or “One who shows the way.” In these type of icons, Mary directs the viewer’s gaze from herself toward the Christ Child, who in turn offers the viewer His blessing.

What is special about Our Lady of Częstochowa is not the uniqueness of its art or the importance of its history, but the amazing accounts of miracles associated with its veneration.

In 1655 the Black Madonna was said to have saved Jasna Gora from a Swedish invasion. It was after this event that the image was declared Queen of Poland. This was later followed by a Canonical Coronation decreed by Pope Clement XI in 1717. Several jeweled crowns were presented and stolen from the image in subsequent wars, only to be replaced by papal and international donations. It is customary for Polish women to wear red coral beads, and thousands of these beads line the walls of her shrine – left in thanksgiving for prayers answered. All the accounts of miracles and cures attributed to the intercession of Our Lady of Częstochowa are preserved in the records of the Pauline Fathers, who have kept the shrine for centuries.

Devotion to the image grew as Pope John Paul II venerated it, offering prayers of petition and thanksgiving in 1979, 1983 and 1991. Perhaps most poignant of all the stories are the countless reports of pilgrims traveling at night to pray for Our Lady’s intercession during the Nazi occupation when Hitler prohibited pilgrimage – among them a young student named Karol Wojtyla, the later Polish pope John Paul II.

Over the intervening centuries Our Lady of Częstochowa has become a very potent symbol – not just for Poland but for those all who are suffering and persecuted – a call to Motherly devotion and, above all, a testament to the resilience of faith.

GIOTTO (C. 1300), ARENA

In Padua, Italy, near an Augustinian monastery, a small church/museum known as the Arena or Scrovegni Chapel contains some of the earliest examples of a profound artistic shift that helped define Christian and Western art for centuries. A cycle of frescoes commissioned to the late medieval artist Florentine Giotto do Bondone cover the walls inside the chapel.

Giotto, as he is known, was acclaimed even in his day as a master who drew “according to nature.” At its beginnings, much of Christian art took its style from Rome, but with the collapse of the empire, through war and iconoclasm Christian art was largely inspired from the East. For most of the first millennia Christian art was characterized by compositions that were generally flat and hierarchic, concentrating the viewer in prayer and veneration through contemplation of the divine portraiture of holy icons.

Giotto’s works ushered in a new standard, a new technique, and a new focus on sacred tradition and what it tells us about the role of Our Lady.

Giotto’s art was the art of fresco, a technique of mural painting usually done on wet plaster. This had been well known and popular among the Greeks and Romans, but persecution and portability had soon led Christians to a different approach. It isn’t until the dawn of the 14th century that we finally see the large-scale return of fresco.

Giotto preferred fresco-secco painting on dry plaster using a binding medium – usually egg. It gave him more time and freedom than an entirely wet technique, allowing him to paint expressive faces full of human emotion. His works became a glimpse into moments in the historic narrative of salvation, replete with blue skies, trees, birds and all the earthly realities of the Incarnation of Our Savior.

Among Giotto’s frescoes in Padua are a series of images depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary – beginning with the non-scriptural narrative involving the tale of Mary’s parents, St. Anne and St. Joachim. These accounts had long been passed down in apocrypha and preserved as part of the deposit of our faith. Now, in a chapel dedicated to Mary, we see the historic story fully played out in time and space for perhaps the first time in a visual media. Long held Christian belief later proclaimed as dogma is brought alive on a scale for all to see and understand. Mary, chosen from the beginning to be the Theotokos, the Mother of God, is immaculately conceived in the womb of St. Anne and born into the world – an event of historic significance celebrated from the earliest centuries.

Presented in a polyscenic image, the frescoes show three moments in time: the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, the New Eve whose “yes” will lead to the Word made flesh, and the salvation of humanity.

fra angelico (C. 1435

When discussing Marian art, images of the Annunciation seem definitive. In these pieces we see captured the very moment when Mary freely gave her “fiat” and God’s promise of Genesis was fulfilled – when the Word became flesh and the redemptive life of Christ entered the world. In studying depictions of the Annunciation, the art of Giovanni da Fiesole seems ubiquitous. Fra Angelico (“Angelic brother”), as history knows him, painted three major altar pieces with this theme during the Florentine art explosion of the first half of the 15th century. Of the three, the Prado Annunciation is perhaps most replete with color and symbolism.

Originally painted in tempera on a wood panel, the piece was commissioned for a side altar for the Convent of San Domenico when Fra Angelico was a friar there. Intended for prayerful meditation, the painting remained in the convent until 1611, when it was sold to the king of Spain and taken to Madrid. The colors, with his use of gold and lapis blue, point to donated money being offered for its original execution. Fra Angelico was able to give his best to this offering.

A viewer of this work needs to pause and go beyond the initial familiar image to see the preaching of a true Dominican. Giovanni da Fiesole is in fact sharing the fruits of his own scriptural contemplations with the viewer – a Lectio Divina writ in crushed pigment, egg binder and gilded leaf.

The Virgin is protected and presented under one arch, while the angel Gabriel in the other arch is vested in a deacon’s dalmatic with knee bent as if approaching the foot of the altar. The vanishing point of the work is shown through an open door between them. Mary is seated, enthroned – Virgin, Consort, Queen and Mother. The Trinitarian presence of the One God is iterated in symbol with the Hand of God in the burst of light shown upper left, the dove of the Holy Spirit on a beam of light visually dissipating as it reaches the Virgin, who now bears in her womb the Son of God. Christ’s eternal existence is reinforced by the image carved in the stone above the center of the room.

One third of the painting shows a garden, a reminder of the perpetual virginity of Mary as well as the Garden of Eden where God cast out our first parents as a result of sin. Here we have the juxtaposition of Eve, Mother of the Living, with Mary the New Eve, the mother of the New Adam who would redeem fallen humanity. Now the beam of light bisecting the work becomes the path through time of our salvation and the fulfillment of the promise made so long ago.

For those who could read the symbolism of flowers, the garden is replete with accurate depictions including crushed roses at the feet of Adam and Eve. These roses, like the little goldfinch in the rod of the arch, point to death and the blood of sacrifice that will become the culminating redemptive act of the Holy Child just conceived.

When Catholics today hear the title “Our Lady of Grace,” we usually envision the countless mass-produced prints and statues in blue pastels that have been ubiquitous in homes for more than a century. Connected to the depiction of Mary on the miraculous medal, the availability of these images exploded with the papal declaration of Marian dogmas and the advent of pulp-paper, color printing and Italian factory art production. These works ushered in a new era for Catholic home devotional art where folk images were widely replaced by affordable, if sometimes low-quality, depictions of Our Lord, Our Lady, saints and angels.

The traditional French title of Our Lady of Grace is in fact much older than this recent popularity and takes its origins from the ancient Christian tradition of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. When in Scripture we hear the Archangel Gabriel address Our Lady as “full of grace,” he is indicating God’s intent from the beginning that she should bear within her the Christ, having been conceived without the stain of Original Sin allowing such an act. Mary’s fiat becomes her free will acceptance that she would offer her humanity to this Hypostatic Union.

Artistic renderings of Our Lady of Grace trace their beginning to the early Medieval period. The first major artistic work now bearing the name is attributed to an Italian/Byzantine icon that shows up in the historic record around 1300. It is called an Eleusa (Virgin of Tenderness) icon because of the way the child Jesus rests tenderly against Mary’s cheek. It bears the Latin initials MR, DI, IHS, and XRS simply meaning, “Mother of God and Jesus Christ.” As with so many other icons before it, it is attributed to Saint Luke and thus protected as a relic. The image is associated with many legends and miracles, and once became the focal point for crusade after the fall of Constantinople.

In 1450, the icon was brought to Cambrai Cathedral, where it was installed on the Feast of the Assumption and has been venerated since in the French tradition as Our Lady of Grace. Art historically, this painting is profoundly influential. It is perhaps the best Marian depiction of the artistic and theological bridge between East and West, Byzantium and Rome. It has attracted a stream of famous pilgrims who commissioned generations of artistic masters, primarily from the North, to produce copies or original art based on the work. Hayne of Brussels, Roger van der Weyden, Petrus Christus, Dieric Bouts and Gerard David all executed paintings derived from the Cambrai Madonna.

Perhaps it is fitting that among the many legends told about the image, it is said to have been hidden in Jerusalem during the early centuries of persecution, then was eventually secreted away to Constantinople in the 5th century. It is unlikely the Cambrai Madonna is that old, but the original icon on which it was based could very well have had such a provenance. The origin of both the art and the title it now bears trace their beginnings to the earliest days of the Church and our understanding of the divine origin of the role of Mary in our salvation.

The brothers Van Eyck (1432)

When we think of famous paintings of the Blessed Virgin Mary, our thoughts often turn to the likes of da Vinci, Raphael and Botticelli. These men and a handful of other giants of the Italian Renaissance seem to command all the press and reproductions. Still, despite the fame of these big names, art historians continuously place a 15th century polyptych altarpiece as among the most important works of art in history: the “Madonnas of the Ghent” altarpiece.

Credited to the illusive Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck, this work from Belgium has become the stuff of novels and fodder for Hollywood thrillers –hunted by Napoleon and coveted by the Nazis. Sometime called the “Adoration of the Mystic Lamb” after the subject of its central panel, it has the dubious distinction of being the most frequently stolen artwork of all time.

The massive reredos was designed to be folded. When closed for penitential seasons, the panels displayed are in muted tones. When opened for Easter and Pentecost, they are awash with vivid color and throughout they are rich in incredible depth and detail and executed at a level rarely achieved before or since. Among the major figures depicted in the work, two are of the Virgin Mary.

Mary on the closed panels is an Annunciation – the moment of the Incarnation when the Holy Spirit descends upon the girl from Nazareth. In her spotless robes and demur expression, she turns from the Angel Gabriel in the perfect personification of the sinless Immaculate Conception. Van Eyck shows us a young woman who is the virginal Ark of the New Covenant, willingly acquiescing as she is overshadowed by the Almighty. Next to her head in Latin is written “Behold the handmaid of the Lord” with the script upside down so God can see what is addressed to Him alone.

In stark contrast and shocking color, the Mary of the open altarpiece is a resplendent Queen of Heaven. Still virginal and still absorbed with the Word of God, she is now shown as Our Lady, a Queen. She sits in a gilded niche at the right hand of a powerful central Christ/Father figure. She is adorned and bejeweled in royal splendor and painted in robes of the deepest, finest blue. Here we see a visual promise of our own redemption. This Mary, as Wordsworth called her, is “our tainted nature’s solitary boast.”

The altarpiece in its entirety has been called perfectly suited for the Liturgy. The enormous work is filled with symbolism and designed for meditation during Mass. In its many panels, believers can contemplate the full panoply of the Paschal Mystery and Mary’s role in salvation history as the woman chosen from all time to be the Mother of God.

When considering how the Virgin Mary has been rendered through two millennia of Christian art, we see how her images have impacted the faithful and the culture in many ways.

Some works of art are of extreme artistic significance, like the Ghent Altarpiece, while others are miraculous and legendary like Our Lady of Czestochowa. Some depictions came at a pivotal moment in history and thus become symbolic and a touchstone for a people like the Madonna of the Salus Populi Romani.

Time and again, many of the most important pieces depicting Our Blessed mother are born of persecution at moments when Christians looked to Our Lady for solace and motherly love during a period of trial. In this context, perhaps no Madonna was born of greater need than those produced and treasured by the Catholics of 17th and 18th century Japan.

Catholicism was introduced to the people of Japan by St. Francis Xavier, who arrived in 1549. Estimates suggest that within 30 years there were as many as 130.000 Japanese Christians. Beginning with the Tokugawa shogunate (c. 1615-1867), power shifted and Christianity was subsequently banned in Japan for over two centuries. In the Nagasaki region during this time, called the Tokugawa or Edo period, people caught practicing the Catholic faith were often executed or imprisoned and their sacred objects seized and destroyed. All households were required to register with local Buddhist groups. To remain alive and pass the faith to their children, many “Kakure Kirishtan” (“hidden Christians”) outwardly appeared to be Buddhist while hiding their true Christian beliefs. Sacred objects such as crosses were camouflaged in the trappings of familiar Buddhist art. One of the most widespread and ingenious images was the development of figures often referred to as “Maria Kannon.”

In these images, Mary was represented and disguised within the trappings of the female version of the Buddhist deity, Kannon (“Mother of Mercy”). Kannon images at this time were sometimes produced holding or even nursing a child. To Buddhist authorities, these images simply blended in and went unnoticed, but to secret Christians they were a tangible link to our Virgin Mother. Modern art historians imply a duel or fused intent for these images and their current popularity suggest that they have taken on that meaning, but their original purpose was linked to the survival of Japanese Christianity through 250 years of attempted eradication. These statues permitted Our Lady to hide in plain sight.

When the first missionary priests returned to Japan in 1865, they found statues of what the people called their “Santa Maria.” They also found a Catholic faith that had survived many generations – passed from parent to child without benefit of priest or sacrament, sustained through the intersession of their Holy Mother and aided through veneration of an image of Mary in a different guise.

Coming Soon